Advanced thermal analysis for quantifying cement hydration phases, carbonation products, and durability assessment in construction materials.[…]

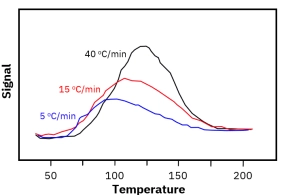

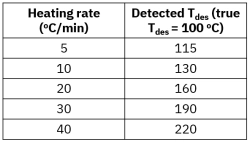

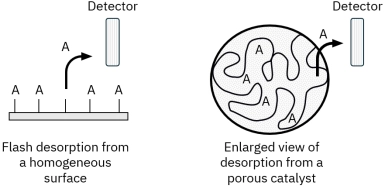

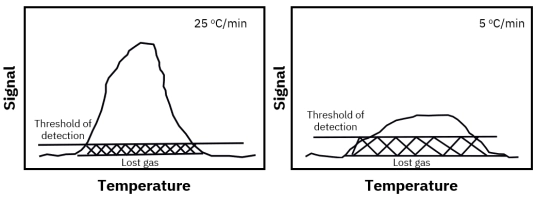

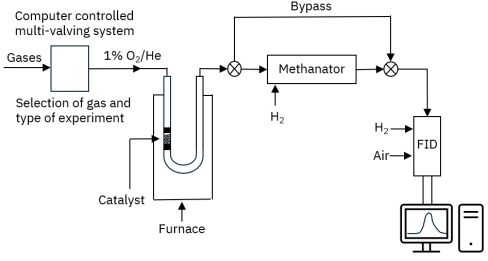

Porous catalysts introduce mass transfer limitations because desorbing molecules may diffuse slowly through pores and re-adsorb on internal surface sites before reaching the detector. This can delay detection and distort kinetic interpretation. Proper control of heating rate, flow rate, and experimental standardization is essential for reliable TPD fingerprinting and catalyst comparison.