Reducing atmospheric CO₂ concentrations remains one of the most pressing challenges in climate science and industrial decarbonization. Carbon Capture and […]

Reducing atmospheric CO₂ concentrations remains one of the most pressing challenges in climate science and industrial decarbonization. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) has emerged as one of the most effective approaches for mitigating CO₂ emissions, with several core technologies under active development: membrane separation, solid adsorption, and liquid absorption.

Membrane separation relies on the selective permeation of gas molecules through materials such as inorganic or organic polymer membranes. Inorganic membranes (e.g., molecular sieves, porous ceramics) offer excellent chemical and thermal stability, but tend to have higher material and processing costs. Organic polymer membranes, while more economical, are limited by thermal

sensitivity, which restricts their use in high-temperature CO₂ capture scenarios.

Solid adsorption captures CO₂ through interactions between gas molecules and the surface of porous materials. Two mechanisms are possible:

Liquid absorption can also be divided into physical and chemical categories.

While chemical solvents offer high capacity and fast absorption rates, several legacy solutions (e.g., KOH and ammonia) face challenges related to equipment corrosion, volatility, and handling safety. Today, amine-based absorbents are the most widely used due to their favorable balance of reactivity, efficiency, and scalability in industrial CO₂ capture.

Organic amines, commonly used in chemical CO₂ absorption systems, contain hydroxyl (–OH) and amino (–NH₂, –NHR, –NR₂) functional groups. The hydroxyl group improves water solubility, while the amino group increases the solution’s pH, enhancing alkalinity and CO₂ absorption potential.

The fundamental mechanism is an acid-base neutralization reaction, in which the weakly acidic CO₂ reacts with basic amines to form a water-soluble salt. This reaction is temperature-dependent and reversible:

Amine Classification and Reactivity

Organic amines are classified by the number of hydrogen atoms substituted on the nitrogen:

The binding strength of CO₂ with these amines generally follows the order:

Primary > Secondary > Tertiary

Primary and Secondary Amines: Carbamate Formation

The widely accepted zwitterion mechanism (Caplow, Danckwerts) describes a two-step reaction:

Here, the zwitterion reacts with a base (e.g., amine, OH⁻, or H₂O) to form a carbamate. The strong C–N bond in the carbamate makes the product highly stable, but also leads to:

Maximum loading for primary/secondary amines is typically 0.5 mol CO₂ per 1 mol amine.

Tertiary Amines: Bicarbonate Formation

Unlike primary and secondary amines, tertiary amines lack reactive hydrogen atoms and do not form carbamates. Instead, they enhance CO₂ hydration and facilitate bicarbonate formation:

This route results in:

2.1 Mass Transfer Mechanism of CO₂ Absorption

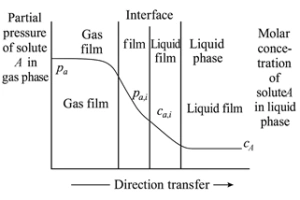

The mass transfer process involved in CO₂ absorption is commonly described using the two-film theory, first proposed by Whitman and Lewis. This model divides the gas–liquid interface into five distinct regions (see Figure 1):

The mass transfer process involved in CO₂ absorption is commonly described using the two-film theory, first proposed by Whitman and Lewis. This model divides the gas–liquid interface into five distinct regions (see Figure 1):

In the bulk gas and liquid phases, turbulence is typically high, ensuring uniform composition. However, as the gas and liquid phases approach the interface, they pass through their respective stagnant film layers, where molecular diffusion becomes the dominant transport mechanism.

The CO₂ absorption sequence follows these steps:

While the two-film theory is widely used and provides a useful conceptual framework, it does have limitations. In systems with free interfaces or high turbulence, the interface becomes unstable and continuously disrupted. Under these conditions, the assumption of two steady, well-defined stagnant films on either side of the interface becomes less accurate. In such cases, convective mixing and interfacial renewal models may offer better descriptions of the actual transport dynamics.

Figure 1. TPD experiment: Tₘₐₓ reflects acid strength (intrinsic acidity); peak area reflects number of acid sites (extrinsic acidity).

Common Probe Molecules

Ammonia (NH₃) is the most commonly used probe due to:

Small kinetic diameter (0.26 nm), allowing access to virtually all acid sites

Strong adsorption on sites of varying strength

Thermal stability over a broad temperature range

Example: Ammonia TPD on H-Y Zeolite

Desorption patterns typically show:

<150°C: Physically adsorbed ammonia (physisorption). This signal can be minimized by conducting adsorption at elevated temperatures (∼100°C).

200–500°C: Chemisorbed ammonia on acid sites. Multiple peaks may appear, reflecting a distribution of acid strengths.

Literature Example

Zi et al. (1) observed that increasing the Si/Al ratio in H-Y zeolites resulted in a stronger high temperature desorption peak, indicating a higher number of acid sites.

Shakhtakhtinskaya et al. (2) correlated desorption signals between 600–900 K (327–627°C) to

Brønsted acid sites, which disappeared upon dehydroxylation.

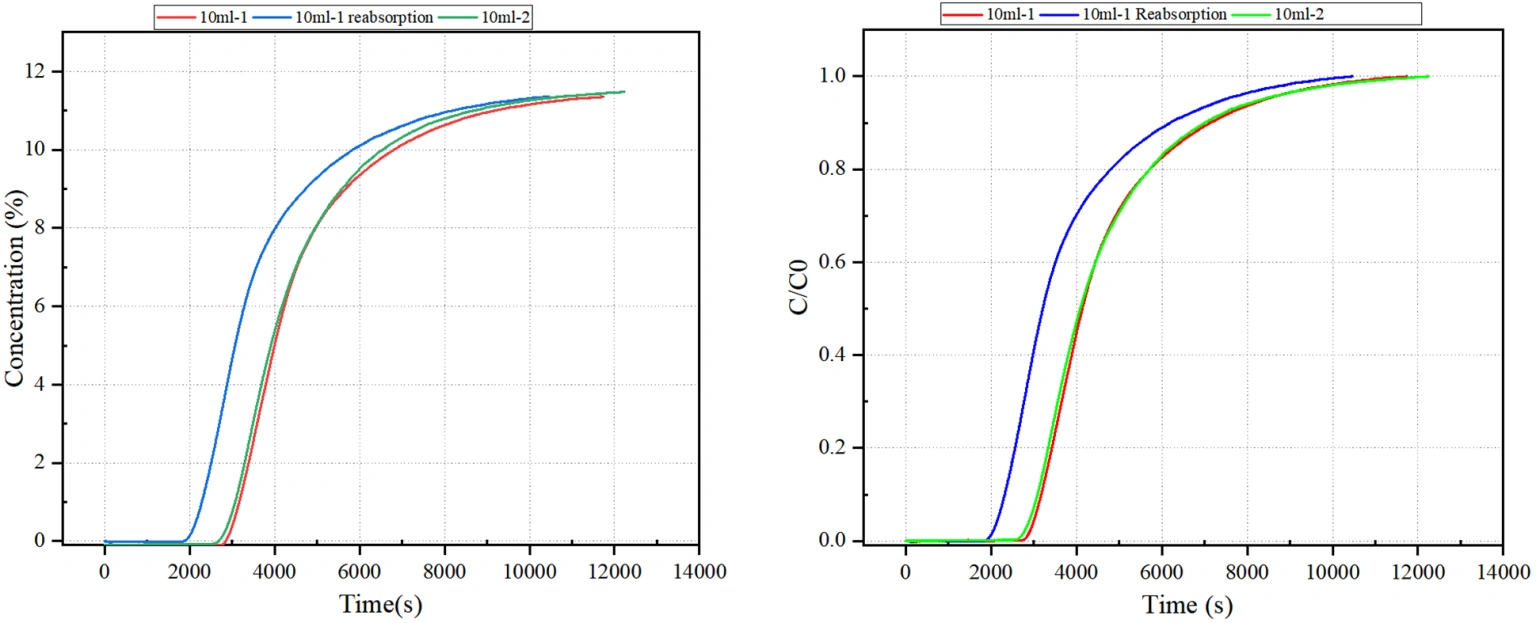

Figure 2 Breakthrough Curve of Ethanolamine MEA

Based on the calculated results presented in Table 2, the measured CO₂ adsorption capacities for the two 10 mL monoethanolamine (MEA) samples were 0.4875 mol/mol and 0.4822 mol/mol, respectively. These values are consistent with the commonly reported commercial MEA capacity of approximately 0.5 mol CO₂ per mol amine, validating the reliability of the test conditions and measurement approach.

Following desorption and re-adsorption (Test 10-1), the measured adsorption capacity decreased to 0.3875 mol/mol, indicating a notable decline in performance after regeneration. This reduction may be attributed to partial thermal degradation of MEA or incomplete recovery of active absorption sites during the desorption cycle.

Table 2 Calculated Adsorption Capacity Results for Ethanolamine MEA

| Adsorption Capacity Results for MEA | |

|---|---|

| Sample Name | Adsorption Capacity (mol CO₂ / mol MEA) |

| 10ml-1 | 0.4875 |

| 10ml-1 (Re-adsorption) | 0.3875 |

| 10ml-2 | 0.4822 |

4.0 Conclusions

This study demonstrates the viability of using monoethanolamine (MEA) as a chemical absorbent for CO₂ capture under ambient conditions. Through a combination of theoretical review and experimental validation using the BTSorb 100 (formally MIX100) breakthrough analyzer, MEA was shown to achieve CO₂ adsorption capacities consistent with commercial expectations (~0.5 mol/mol). While regeneration was successful, a decline in adsorption performance after the desorption cycle suggests some loss in efficiency, likely due to thermal degradation or incomplete solvent recovery.

The data confirms that MEA remains a strong candidate for CO₂ absorption systems, especially when optimized with temperature control and proper regeneration protocols. Future improvements may be achieved through blending with secondary or tertiary amines, use of corrosion inhibitors, or incorporation of nanomaterials and catalysts to reduce energy consumption and enhance cycling performance. These directions represent promising opportunities for scaling liquid-phase CO₂ capture in industrial applications.

5.0 References

[1] Wang J., Huang L., Yang R., et al. Recent advances in solid sorbents for CO₂ capture and new development trends. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014, 7: 3478–3518.

[2] Venna S.R., Carreon M.A. Highly permeable zeolite imidazolate framework-8 membranes for CO₂/CH₄ separation. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2010, 132(1): 76–78.

[3] Huang Yuhui. Research on the Degradation of Mixed Amine Absorbents for Flue Gas CO₂ Chemical Absorption Technology [D]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2021.

[4] Wang Dong, et al. Research progress on solid and liquid adsorbents for carbon dioxide capture.