Building on our previous overview of SSITKA (Steady-State Isotopic Transient Kinetic Analysis), this article delves into the core principles and computational methods behind […]

Abstract

Hydrogen’s high gravimetric energy density (120 MJ/kg) positions it as a critical energy carrier for the transition to clean energy systems. However, its extremely low density at ambient conditions significantly limits its volumetric energy density, complicating storage and transportation. Among various hydrogen storage strategies, solid-state hydrogen storage has emerged as the most promising due to its safety, efficiency, and volumetric advantages. This application note presents a comprehensive analysis of hydrogen storage materials—including Mg-based hydrides, rare earth alloys, carbon-supported systems, and MOFs—evaluated using AMI advanced sorption instrumentation.

Introduction

The volumetric energy density of hydrogen is limited by its low density at ambient conditions—0.0824 kg/m³ compared to 1.184 kg/m³ for air. Methane and gasoline have volumetric energy densities of approximately 0.04 MJ/L and 32 MJ/L, respectively. Hydrogen’s flammability, diffusivity, and explosion risks further challenge its storage [1].

Three primary hydrogen storage methods are commonly used:

Solid-state hydrogen storage stands out for safety, energy density, and moderate operating conditions, relying on physical adsorption or reversible chemical bonding. The development of high-performance materials is now central to advancing this technology.

Material Classes and Storage Mechanisms

Magnesium hydride (MgH₂) offers a theoretical hydrogen capacity of ~7.6 wt% and excellent stability under ambient conditions. However, its high desorption enthalpy (ΔH = 76 kJ/mol) and poor kinetics limit practical use. Agglomeration during cycling also reduces reversibility.

Approaches to Improve MgH₂ Performance:

Alloying Mg with elements like Ni, La, Ce, or Pr forms metastable phases, reducing reaction temperatures and improving kinetics.

Figure 1 Schematic Diagram of SSITKA Experimental Device

Most SSITKA experiments today rely on microreactor-based systems that are either manual or semi-automated, often leading to operator-induced variability. The AMI 300TKA system addresses this challenge by enabling fully integrated SSITKA experiments through dedicated gas circuit design and coupled mass spectrometry, as shown in the software interface in Figure 2. Transient switching is achieved using a four-way valve, which alternates between two feed streams: Aux Gases and Blend Gases. These streams introduce either the unlabeled reactant (12CO) or the isotopically labeled reactant (13CO). Upon valve switching, the system seamlessly transitions from 12CO to 13CO under steady-state conditions.

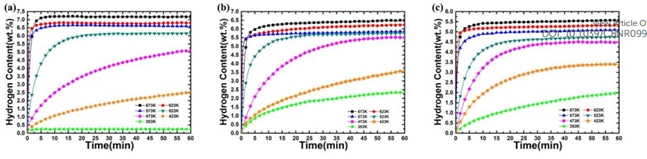

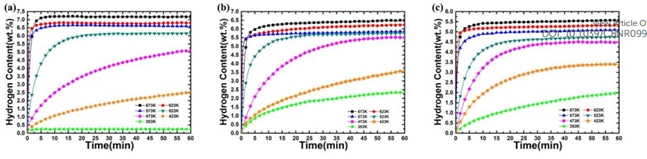

Figure: Adsorption Kinetics at Different Temperatures & Cyclic Adsorption Performance

Carbon materials improve dispersion, prevent agglomeration, and enhance hydrogen kinetics via electron transfer and surface defects.

LaNi₅ offers:

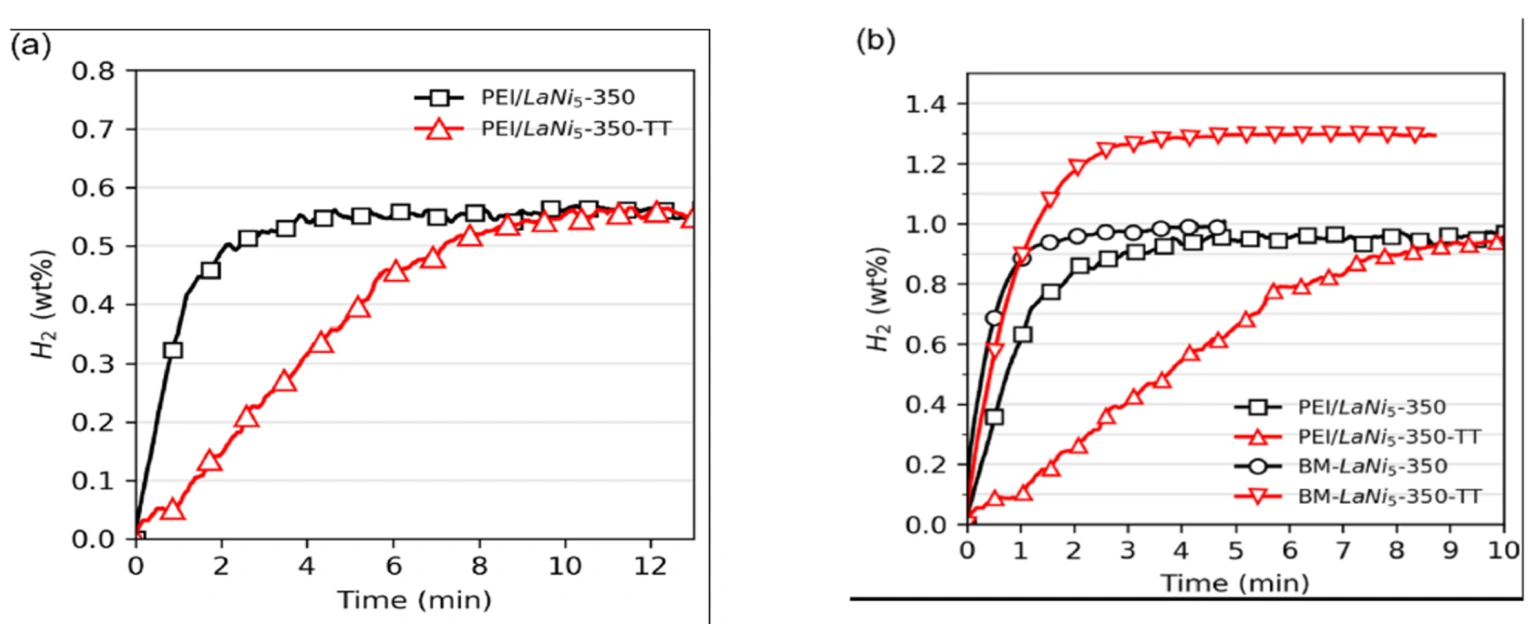

Zhu et al. [7] and Liu et al. [8] showed LaNi₅₋ₓCoₓ alloys maintain structure and capacity over 1000 cycles. Substituting La with Pr, Ce, or Gd improves equilibrium pressure and kinetics. Neto et al. [9] demonstrated improved absorption kinetics in PEI-LaNi₅ composite films at 40°C/20 bar.

Figure: Effects of Different Annealing Conditions on Hydrogen Absorption Kinetics

MOFs combine high porosity, surface area, and tunable pore chemistry for physisorption-based H₂ storage.

Experimental Evaluation Using AMI

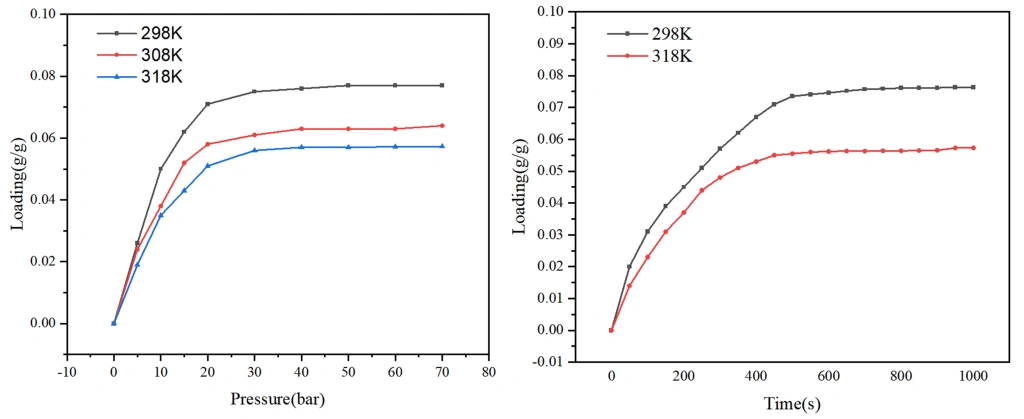

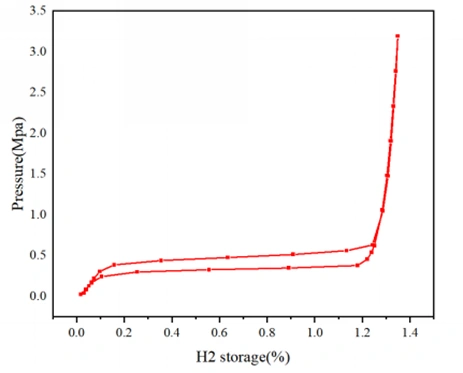

Using the RuboSorp MPA, AMI’s high-pressure volumetric gas sorption analyzer, LaNi₅ was tested at room temperature under pressures up to 3 MPa. Results showed rapid hydrogen uptake at low pressures (to 1.35 wt%), saturating at six hydrogen atoms per unit cell—consistent with theoretical expectations. An observable hysteresis loop indicated structural changes in LaNi₅ during hydrogen cycling.

Figure: Pressure vs. hydrogen uptake curve for LaNi₅ using RuboSorp MPA

Using the RuboSorp MSB, a high-precision magnetic suspension balance system, real-time weight changes during hydrogen adsorption were recorded. The MSB provides higher accuracy than traditional volumetric systems and enables visualization of subtle structural changes through its unique high-resolution volume acquisition capabilities.